Wow Pluto How Pluto Became a Planet Again Full Video

For 76 years, Pluto was the beloved ninth planet. No 1 cared that information technology was the runt of the solar system, with a moon, Charon, half its size. No one minded that information technology had a tilted, eccentric orbit. Pluto was a weirdo, just it was our weirdo.

"Children place with its smallness," wrote science writer Dava Sobel in her 2005 book The Planets. "Adults relate to its inadequacy, its marginal being every bit a misfit."

When Pluto was excluded from the planetary brandish in 2000 at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, children sent hate mail to Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the museum's planetarium. Besides, there was a popular uproar when 15 years ago, in August 2006, the International Astronomical Union, or IAU, wrote a new definition of "planet" that left Pluto out. The new definition required that a body ane) orbit the sun, 2) take plenty mass to be spherical (or close) and 3) accept cleared the neighborhood around its orbit of other bodies. Objects that meet the first ii criteria but non the 3rd, similar Pluto, were designated "dwarf planets."

Scientific discipline is not sentimental. It doesn't intendance what you're fond of, or what mnemonic you learned in elementary school. Scientific discipline appeared to have won the day. Scientists learned more virtually the solar organisation and revised their views accordingly.

"I believe that the determination taken was the correct one," says astronomer Catherine Cesarsky of CEA Saclay in French republic, who was president of the IAU in 2006. "Pluto is very different from the 8 solar organisation planets, and it would take been very difficult to keep irresolute the number of solar arrangement planets as more massive [objects beyond Neptune] were existence discovered. The intention was not at all to demote Pluto, only on the contrary to promote information technology equally [a] prototype of a new class of solar system objects, of corking importance and involvement."

For a long time, I shared this view. I've been writing about Pluto since my very first newspaper gig at the Cornell Daily Sun, when I was a inferior in higher in 2006. I interviewed some of my professors well-nigh the IAU's decision. One, planetary scientist Jean-Luc Margot, who is now at UCLA, chosen it "a triumph of science over emotion. Scientific discipline is all nigh recognizing that earlier ideas may have been wrong," he said at the fourth dimension. "Pluto is finally where it belongs."

Simply another, planetary scientist Jim Bell, now at Arizona Country University in Tempe, thought the decision was a travesty. He still does. The idea that planets have to articulate their orbits is specially deadening, he says. The ability to collect or cast out all that debris doesn't just depend on the trunk itself.

Everything with interesting geology should exist a planet, Bell told me recently. "I'thou a lumper, not a splitter," he says. "Information technology doesn't thing where y'all are, information technology matters what you are."

Not everyone agrees with him. "15 years ago we finally got it right," says planetary scientist Mike Brown of Caltech, who uses the Twitter handle @plutokiller because his inquiry helped knock Pluto out of the planetary pantheon. "Pluto had been incorrect all forth."

Just since 2006, nosotros've learned that Pluto has an temper and perhaps even clouds. It has mountains made of water water ice, fields of frozen nitrogen, marsh gas snow–capped peaks, and dunes and volcanoes. "It's a dynamic, complex world unlike any other orbiting the sun," journalist Christopher Crockett wrote in Science News in 2015 when NASA's New Horizons spacecraft flew by Pluto.

The New Horizons mission showed that Pluto has fascinating and agile geology to rival that of whatsoever rocky world in the inner solar system. And that solidified planetary scientist Philip Metzger'south view that the IAU definition missed the marking.

"At that place was an immediate reaction confronting the dumb definition" when it was proposed, says Metzger, of the Academy of Key Florida in Orlando. Since and then, he and colleagues have been refining their views: "Why do nosotros have this intuition that says that it's dumb?"

Retelling the tale

It turns out that the "nosotros merely learned more than" narrative isn't actually true, Metzger says. Though the official story is that Pluto was reclassified considering new data came in, it's not that simple. Teaching that narrative is bad for science, and for scientific discipline education, he says.

The truth is, there's no single definition of a planet — and I'k beginning to believe that'due south a skilful thing.

For centuries, the word "planet" was a much more inclusive term. When Galileo turned his telescope at Jupiter, any largish moving body in the sky was considered a planet — including moons. When astronomers discovered the rocky bodies nosotros now phone call asteroids in the 1800s, those too were called planets, at least at get-go.

Pluto was considered a planet from the very beginning. When Clyde Tombaugh, an amateur astronomer from Kansas newly recruited to the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz., spotted it in photos taken in January 1930, he rushed to the observatory director and declared: "I take constitute your Planet X."

The discovery was no accident. In 1903, U.S. astronomer Percival Lowell hypothesized that a hidden planet seven times the mass of Globe orbited 45 times further from the sun. Lowell had searched for what he called Planet X until he died in 1916. The search connected without him.

The new planet was thought to be "black as coal, nearly as dumbo equally atomic number 26, twice as dense equally the heaviest earthly surface rocks," Science News Letter, the predecessor of Science News, reported in 1930.

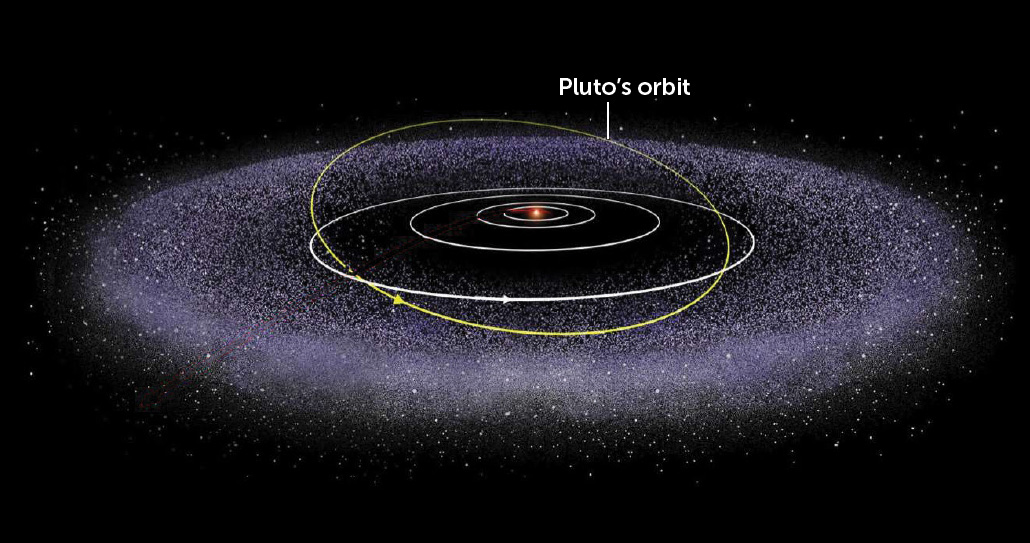

Further research showed Lowell had grossly overestimated Pluto's mass: It'southward more like 1 five-hundredth the mass of Earth. Things got even weirder when scientists realized Pluto wasn't alone out there. In 1992, an object about a tenth the diameter of Pluto was found orbiting the sun "in the deep freeze of space well beyond the orbits of Pluto and Neptune," as Science News described information technology.

Since then, more than 2,000 icy bodies accept been plant hiding in that frigid zone dubbed the Kuiper Belt, and there are many more out at that place. Awareness of Pluto'southward neighbors brought new questions: What characteristics could unite these foreign new worlds with the more familiar ones? And what sets them apart? With so many new objects coming into focus, at that place was a growing desire for a formal definition of "planet."

In 2005, Brown spotted the first of the Kuiper Belt bodies that seemed to exist larger than Pluto. If Pluto was the ninth planet, and then surely the new discovery, nicknamed Xena (in honor of the TV show Xena: Warrior Princess), should exist the 10th. Just if Xena was an icy leftover from the formation of the solar arrangement undeserving of the "planet" title, so also was Pluto.

Tensions over how to categorize Pluto and Xena came to a caput in 2006 at a coming together in Prague of the IAU. On the last 24-hour interval, August 24, after much begrudging argue, a new definition of "planet" was put to a vote. Pluto and Xena got the boot. Xena was aptly renamed Eris, the Greek goddess of discord.

Textbooks were revised, posters were reprinted, only many planetary scientists, specially those who study Pluto, never bothered to alter. "Planetary scientists don't use the IAU's definition in publishing papers," Metzger says. "We pretty much just ignore it."

In part that might exist cheek, or spite. Just Metzger and colleagues remember there's good reason to reject the definition. Metzger, Bell and others — including Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Plant, the planetary scientist who led the New Horizons mission and has argued since before the discovery of the Kuiper Belt that the solar arrangement contains hundreds of "planets" — make their case in a pair of recent papers, ane published in 2019 in Icarus and one forthcoming.

After examining hundreds of scientific papers, textbooks and letters dating dorsum centuries, the researchers show that the manner scientists and the public have used the give-and-take "planet" has changed over time, merely not in the mode nigh people think.

In and out

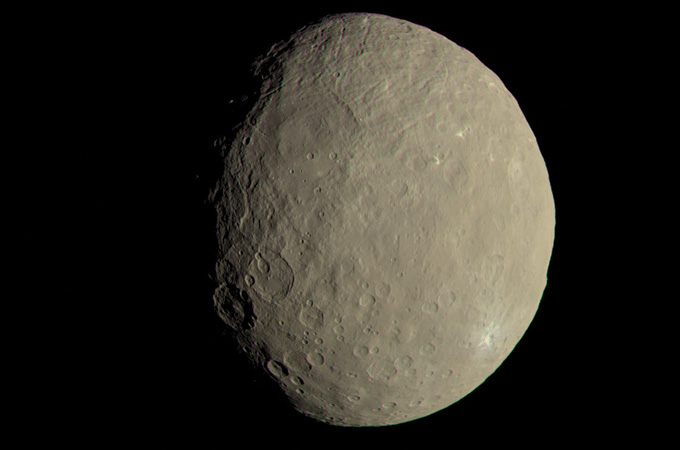

Consider Ceres, the first of what are now known equally dwarf planets to be discovered. Located in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, Ceres was considered a planet after its 1801 discovery, too. Information technology'southward frequently said that Ceres was demoted after astronomers found the balance of the bodies in the asteroid belt. Past the end of the 1800s, with hundreds of asteroids piling up, Ceres was stripped of its planetary championship cheers to its neighbors. In that sense, the story goes, Ceres and Pluto suffered the same fate.

Simply that'southward not the real story, Metzger and colleagues found. Ceres and other asteroids were considered planets, sometimes dubbed "minor planets," well into the 20th century. A 1951 article in Science News Letter alleged that "thousands of planets are known to circle our sun," although most are "small fry." These "baby planets" tin be as pocket-sized equally a urban center block or as wide every bit Pennsylvania.

Information technology wasn't until the 1960s, when spacecraft offered better observations of these bodies, that the term "pocket-sized planets" fell out of fashion. While the largest asteroids still looked planetlike, about small asteroids turned out to be lumpy and irregular in shape, suggesting a unlike origin or different geophysics than bigger, rounder planets. The fact that asteroids didn't "clear their orbits" had nothing to do with the name modify, Metzger argues.

And what about moons? Scientists called them "planets" or "secondary planets" until the 1920s. Surprisingly, it was nonscientific publications, notably astrological almanacs that used the positions of celestial bodies for horoscope readings, that insisted on the simplicity of a limited number of planets moving through the fixed sphere of stars.

Metzger thinks that older definition of a planet that included moons was forgotten when planetary scientific discipline went through a "Great Low" between almost 1910 and 1950. So many asteroids had been discovered that searching for new ones or refining their orbits was getting ho-hum. Telescopes weren't good enough to start exploring asteroids' geology yet. Other parts of space science were way more exciting, so attention went there.

Simply new information that came with infinite travel brought moons back into the planetary fold. Starting in the 1960s, "planet" reappeared in the scientific literature as a description for satellites, at least the big, round ones.

Existent-globe usage

The planet definition that includes sure moons, asteroids and Kuiper Belt objects has had staying power because it's useful, Metzger says. Planetary scientists' piece of work includes comparing a identify like Mars (a planet) to Titan (a moon) to Triton (a moon that was probably born in the Kuiper Chugalug and captured by Neptune long ago) to Pluto (a dwarf planet). It's scientifically useful to have a give-and-take to depict the cosmic bodies where interesting geophysics, including the conditions that enable life, occur, he says. There's all sorts of extra complication, from mountains to atmospheres to oceans and rivers, when rocky worlds grow big enough for their own gravity to make them spherical.

"We're not challenge that we take the perfect definition of a planet and that all scientists ought to adopt our definition," he adds. That's the same error the IAU made. "We're saying this is something that ought to be debated."

A more inclusive definition of "planet" would besides give a more than authentic concept of what the solar organization is. Emphasizing the eight major planets suggests that they dominate the solar arrangement, when in fact the smaller stuff outnumbers those worlds tremendously. The major planets don't even stay put in their orbits over long time-scales. The gas giants take shuffled effectually in the past. Teaching the view of the solar arrangement that includes merely eight static planets doesn't do that dynamism justice.

Caltech's Brownish disagrees. Having the gravitational oomph to nudge other bodies in and out of line is an important characteristic of a earth, he says. Plus, the eight planets conspicuously dominate our solar organisation, he says. "If y'all dropped me in the solar system for the starting time time, and I looked around and saw what was there, nobody would say anything other than, 'Wow, there are these 8 — choose your word — and a lot of other niggling things.' "

Thinking of planets that fashion leads to big-picture questions almost how the solar system put itself together.

One common argument in favor of the IAU'due south definition is that it keeps the number of planets manageable. Can you imagine if at that place were hundreds or thousands of planets? How would the boilerplate person keep track of them all? What would we print on lunch boxes? I'm non making fun of this idea; every bit an astronomy writer who has been obsessed with space since I was 8, I would be reluctant to turn people off to the planets.

But Metzger thinks education just eight planets risks turning people off to all the remainder of space. "Back in the early 2000s, at that place was a lot of excitement when astronomers were discovering new planets in our solar system," he says. "All that excitement ended in 2006." But those objects are still out at that place and are nonetheless worthy of involvement. By now, there are at least 150 of these dwarf planets, and most people have no inkling, he says.

This is the argument I find most compelling. Why exercise we need to limit the number of planets? Kids can memorize the names and characteristics of hundreds of dinosaurs, or Pokémon, for that matter. Why non encourage that for planets? Why not inspire students to rediscover and explore the infinite objects that near entreatment to them?

I've come to call back that what makes a planet may merely exist in the middle of the beholders. I may exist a lumper, not a splitter, too.

Source: https://www.sciencenews.org/article/pluto-planet-vote-status-definition-demotion

0 Response to "Wow Pluto How Pluto Became a Planet Again Full Video"

Post a Comment